- The Moneycessity Newsletter

- Posts

- AVOID These 9 Mind Traps To BEAT 99% of Investors in 2025

AVOID These 9 Mind Traps To BEAT 99% of Investors in 2025

A lack of investing expertise is NOT what holds back most investors. Understanding the nine investing psychological pitfalls is THE low-hanging fruit to boost your returns.

The average investor is missing out on 50% greater gains, not because of technical abilities or knowledge, but because of psychology. There are 9 tricks our minds play on us that cause us to screw up our investments.

Watch the extended version HERE.

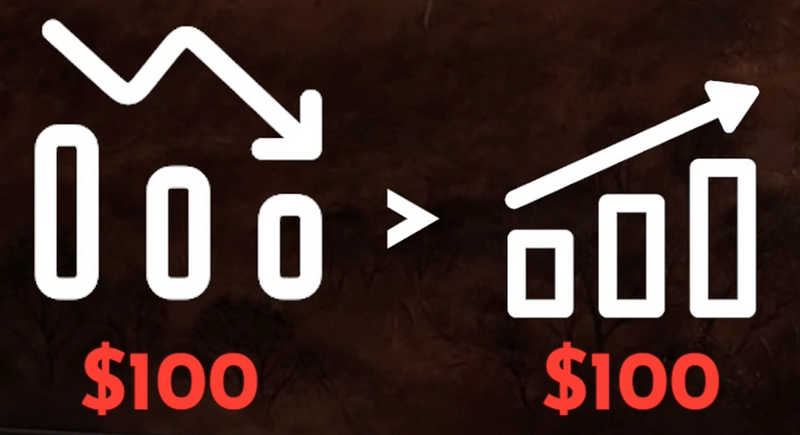

1. Mental Accounting

If you are at the casino and you brought $100 as your bankroll for the trip — if you lose that cash you are done gambling.

The first game you hit is a cheap slot machine and you get lucky with a $100 gain. Now you are up to $200.

Mental accounting is where you view the $100 profit as fundamentally different than the original $100 that you brought. You might make riskier bets with the profit than your original $100 because you are playing with “house money”.

Mental Account — Illustration by author

In reality, these two benjamins are identical and should be treated as such. Mental accounting causes investors to make irrational investments into overly or underly risky positions. It works both ways.

2. Loss Aversion

When the stock market starts to drop, panic selling begins. Even though the best times to invest throughout history are during market crashes, our instincts take over. Humans naturally fear losing more than we desire for an equivalent gain.

Loss Aversion — Illustration by author

I will never forget the time I lost a $100 Christmas bonus that I received in a paycheck. I was stoked to find there. It was a complete surprise. But the joy was nowhere close to the agony I felt when I reached into my pocket where I left it to find nothing. The pain was 100 times the joy.

This graph shows investor behavior during the stock market crashes of 2000 and 2008. The red line is the S&P 500 stock price and the blue line is the amount of cash pulled out of the market.

Cash VS Stock Holdings

Notice the absolute peak of the blue line is right at the absolute lowest point of the red line. It should be the opposite!

The very bottom is the best time to buy but investors just cannot bring themselves to do it because of loss aversion.

3. Narrow Framing

I love steak. When I buy my groceries for the week, you can find me drooling over the wagyu. If I could afford it, I would be tempted to buy nothing but A5 Wagyu.

But, this would be narrow framing. I might love A5 wagyu steak, but in the context of my diet, it would not be a good idea. Steak all day every day would end up not tasting good in the end anyway.

The same is true for investing. My favorite thing to do is analyze individual stocks that are high-risk and high-reward. But my portfolio can not survive with that allocation.

I need to have some cash for emergencies, some index funds in my 401k, and some fixed income down the road. Even though individual stocks are my favorite, I have to widen my frame of reference to avoid focusing on just one area of my portfolio.

4. Diversification

Just because you are invested in many different assets does not mean that you are properly diversified. Lumping together many super-risky investments does not necessarily reduce your risk.

This is exactly what went wrong in the financial crisis of 2008. Improper diversification sets investors up for crushing losses.

2008 Housing Bubble Crash

5. Anchoring

I have been guilty of this psychological bias. When I buy a stock, I give the purchase price too much power. I hate to sell that stock unless it is at least the same price that I bought it.

However, the purchase price has no relevance to whether or not an investment is currently at a good price. When other investors are deciding whether or not to buy my shares of stock, they will consider:

The profitability of the company

The quality of the product

The economy as a whole

But you know what they are not thinking about? My purchase price. My purchase price is irrelevant to whether or not I should sell that stock.

Anchoring — Illustration by author

For instance, if I bought a house for $250K and the next day a waste processing plant is built next door, that would suck. Of course, I would want to sell my house for $250K so I don’t lose money but that would be incredibly unlikely. If I reject an offer for $230K, I will have fallen prey to anchoring — making a financial decision based on an irrelevant data point.

6. Media Response

The media is incentivized to hold our attention. The stories that are the most sensational will naturally rise to the top. Another year of typical stock market returns is not a sensational story, but it is the most likely.

50 Years of S&P500 Returns

This graph shows the returns in the S&P 500 over a 50-year period going back to 1970. There are only 11 years with negative returns.

Therefore, most media coverage about projected stock market performance will be unlikely. Investors with a strong media response will be pulling money out of the market too often, resulting in lower returns.

If I am being swayed by the countless TikTok influencers talking about a market crash, I will be pulling my money out of the market too often. And I will miss out on the 39 out of 50 years of positive market gains!

7. Regret

Today, this is better described as FOMO — fear of missing out.

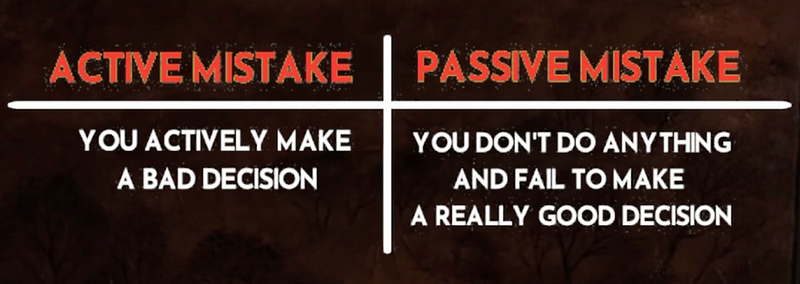

At the most basic level, there are two types of mistakes: active and passive.

Active is where you actively make a bad decision

Passive is where you don’t do anything and miss the chance to make a really good decision

Types of Mistakes — Illustration by author

Investors who experience FOMO are being pushed into making an active mistake because they are trying to avoid a passive mistake — even though active mistakes are much more costly.

Falling for the regret principle often has investors staying in an investment too long or continuing to funnel more money in because they do not want to regret missing out on the recovery.

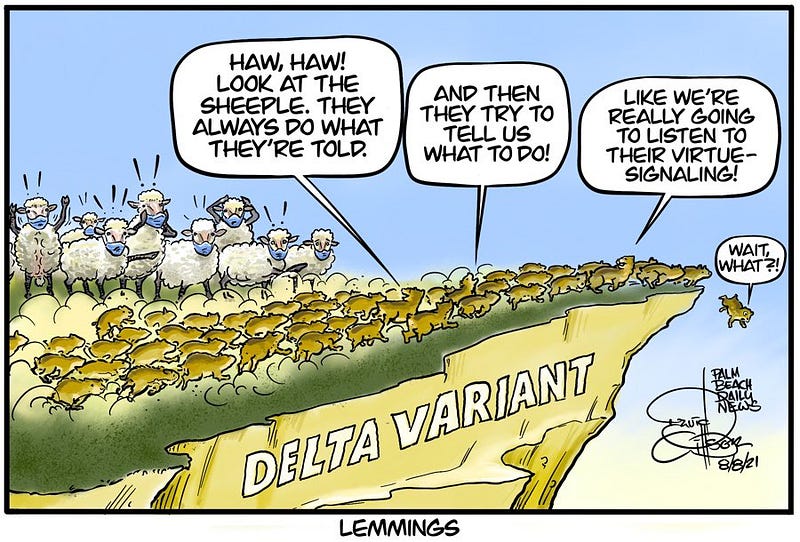

8. Herding

As mammals, we have an evolutionary reaction to run with the herd. In the jungle, if you see ten people running for their lives, you better run too.

In this case, the passive error is much more costly.

If you don’t run and those ten people are running from a lion, the downside is you die. If you do run and those ten people were running from a squirrel because they heard a noise coming from a bush, the downside is you got some exercise.

Herding mentality works for the jungle but we did not evolve to have the best investing practices.

With investing, running out of the stock market does have a cost—opportunity cost. Following the herd out of the market or into overpriced stocks will hurt our investing returns.

9. Optimism

When I am on vacation and renting a car, the rental place always tries to get me to buy insurance. But I know I am a good driver so I never pay for it. Nothing is going to happen, the trip is just a week long.

Optimision — Illustration by author

In this scenario, I am being overly optimistic. I may be a good driver but there will be a thousand other cars on the road and I will be in an unfamiliar place! The external risks out of my control do not disappear just because I am involved.

If you have already been hit by one of these biases and you’re sitting on a stock loss, do not fear. There is a way to get out and get something out of it. I shared my best practices for exiting a bad stock position HERE.

Catch you on the flip side.

Reply